History of Traffic

There’s actually a whole history behind how traffic in our City has evolved into what it is today – a smooth, efficient, and expeditious way of getting from one place to another. Believe it or not, that’s true; at least compared to what it used to be.

Until the end of the 19th Century, traffic in New York City was largely uncontrolled. Carriages and wagons dashed about in every direction, and runway horses added to the chaos with alarming frequency. Getting across a busy street could be a real challenge, and the constant hazard to pedestrians led in the 1860’s to the formation of the first traffic-related unit in the NYPD, the famous Broadway Squad”. The officers of the Broadway Squad were the largest and most imposing in the Department (the minimum height was six feet), and their primary duty was nothing other than to escort pedestrians safely across Broadway in Manhattan between Bowling Green and West 59th Street.

A new wrinkle in traffic control was added by the bicycle craze of the 1890’s, when large numbers of cyclists took to the City’s streets. To control the speed-demon “wheelmen” who exceeded the New York City speed limit of 8 miles per hour (approximately 13 kph), in December of 1895, Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt organized the police Department’s old Bicycle Squad, which quickly acquired the nickname of the “scorcher” Squad. The Scorcher Squad soon found itself with the responsibility of enforcing the speed regulations not just for Bicycles, but for the newest toy of the wealthy: the automobile. A Scorcher Squad officer stationed in a booth would record the speeds of passing vehicles. When excessive speed was observed, he would telephone ahead to the next booth, and a uniformed officer would be dispatched on a bicycle to stop the offender. Traffic summonses did not then exist, so speeders caught by “Scorchers” were arrested on the spot and brought before the judge.

The difficulty that the public experienced attempting to negotiate the maze of people, horses, and bicycles on streets that were often unpaved, muddy, or dusty found some relief when the subway system began operating in October of 1904. Yet the great number of horses on the streets of that year was clearly evident by that fact that the NYPD’s Mounted Division alone had by that time reached its all-time high of 800 officers, with its primary unit being the “Traffic Squad”. Still, automobiles were becoming increasingly popular, and no longer just with the wealthy. And with the great numbers of motor cars and trucks jamming the streets, it was not unusual to see traffic disputes settle by drivers “duking it out”, and still further tying up traffic. It soon became apparent that vehicular traffic regulations were absolutely necessary.

In December 1908, Police Commissioner Bingham was given the responsibility of creating the first traffic regulations after his authority had been specifically extended to encompass this area. The original “rules of the road” that were adopted included keeping to the right so that slower-moving vehicles could be passed on the left, and signaling one’s intentions by extending or raising the hand (or the whip) before slowing, stopping, or turning. Enforcing these regulations, however, was a little difficult at first as the state legislature did not give the Police Department the power to issue summonses for traffic infractions until 1910.

In December 1908, Police Commissioner Bingham was given the responsibility of creating the first traffic regulations after his authority had been specifically extended to encompass this area. The original “rules of the road” that were adopted included keeping to the right so that slower-moving vehicles could be passed on the left, and signaling one’s intentions by extending or raising the hand (or the whip) before slowing, stopping, or turning. Enforcing these regulations, however, was a little difficult at first as the state legislature did not give the Police Department the power to issue summonses for traffic infractions until 1910.

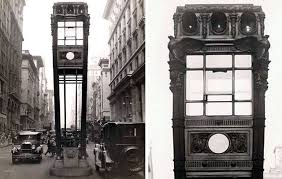

While it is not known how exactly many summonses were issued at that time, the number of motor vehicles in New York City had already mushroomed by 1912 to 38000. (Today there are over 2 million vehicles of all types registered in the City, in addition to the uncounted vehicles that commute from the suburbs every day). Many of the traffic summonses issued today are for “running” the red lights, but no driver today would expect a summons for driving past a green light. However, this has not always been the case. The first traffic control devices at intersections in New York City were installed in 1915. They were four-armed manually-operated semaphores with the words “STOP” and “GO” painted on their arms. A far grander device, however, made its appearance the following year. In 1916, the first traffic tower was erected in the middle of the intersection of Fifth Avenue and 42th Street. Standing inside a booth 16-inch (40 centimeters) diameter electric lamps positioned on top of the booth. Three of these 500-watt lamps were red, amber, and green, and faced north; while three similarly colored lamps faced south.

However, at that time, a red light in New York City meant traffic in all directions had to stop. An amber light meant cross-town traffic would have to stop so that north and southbound traffic could pass. A green light would stop north and south bound lanes of traffic so that cross-town traffic could proceed. The difficulty in understanding this confusing color sequence was compounded by neighboring towns using another system, the “railroad signal designation” sequence of red for stop, green for go, and yellow for slow. It came as no surprise that out-of-town drivers headed north on Madison Avenue were not thrilled to receive a summons for “passing a green light”.

The confusion died down only after the City agreed in 1924 to utilize the railroad system that by then had been adopted by most towns in the United States. Meanwhile, there were now 50 traffic towers throughout the City. Seven of these towers had been cast of bronze at the cost of $200,000 and were erected along 5th Avenue during the winter of 1922.

But Traffic Towers, like the semaphore system, cost a lot of money to operate. The towers required 100 officers working 16-hour per day, and that costing the City an estimated of $ 250,000 a year in salaries, equipment, and maintenance). In the case of traffic on Fifth Avenue, the towers took the two center lanes of the six-lane road which greatly constricted the flow of traffic. It was these reasons that the then NYC Department of Plant and Structures recommended a major change in 1924 that would revolutionize traffic forever – The electrically synchronized signal light.

By the following year, 75 experimental traffic lights atop pedestal posts had been installed at corners of various major Midtown intersections. This system proved so successful that by 1934, the number of traffic lights in the City had grown to 7700. Although the art of timing the light sequence (or “staggering”) of the traffic devices took many years to refine, its resulting success actually reduced the time needed to cross Manhattan by some eight minutes.

A fully automated traffic light system could not have come at a better time as the volume of traffic was about to increase dramatically. In 1927, The Holland tunnel opened, thus increasing the number of cars driving into the City. In 1931, the George Washington Bridge was placed into service. By 1934, the volume of traffic in New York City had further exploded with the completion of the first four sections of the West Side Highway from Canal Street to West 48th Street. Construction of the Lincoln Tunnel also began in 1934 and was soon followed by Construction of the East River Drive in 1935. In 1936 was the construction of both Queens-Midtown Tunnel and Tri-borough Bridge. It was obvious that with the new influx of mobile commuters, an efficient system of expediting traffic had become essential for the City’s survival. That’s also why the need of Traffic Agents in the City is very important.

Traffic Enforcement Agents (TEA) had been employed by the City of New York as early as 1962 working alongside with Department of Transportation (D.O.T) to enforce the rules and regulations of New York City. Over the years, we have been referred to as brownies or meter maids; the proper civil service title is Traffic Enforcement Agent, code number 71651. In 1996, Traffic Enforcement Agents merged with the New York Police Department (NYPD) to continue working and enforcing the rules and regulations of the City of New York. Our position as Enforcement Agent was created because of the burden of traffic enforcement on police officers. The creation of TEAs freed up police officers to deal with harsher penal code violations, such as murders, rapes, robberies, etc. An all-female work unit in its inception, the agents were originally attached to the Department of Transportation working out of police precincts. In 1966, men were offered the position. The uniform, which was originally blue, was changed to brown by then Transportation Commissioner Benjamin Ward. In 1972, Commissioner Ward is also credited with instituting and promoting the level two position of traffic control.

Traffic Enforcement Agents (TEA) had been employed by the City of New York as early as 1962 working alongside with Department of Transportation (D.O.T) to enforce the rules and regulations of New York City. Over the years, we have been referred to as brownies or meter maids; the proper civil service title is Traffic Enforcement Agent, code number 71651. In 1996, Traffic Enforcement Agents merged with the New York Police Department (NYPD) to continue working and enforcing the rules and regulations of the City of New York. Our position as Enforcement Agent was created because of the burden of traffic enforcement on police officers. The creation of TEAs freed up police officers to deal with harsher penal code violations, such as murders, rapes, robberies, etc. An all-female work unit in its inception, the agents were originally attached to the Department of Transportation working out of police precincts. In 1966, men were offered the position. The uniform, which was originally blue, was changed to brown by then Transportation Commissioner Benjamin Ward. In 1972, Commissioner Ward is also credited with instituting and promoting the level two position of traffic control.

In a major metropolis such as New York City, traffic flow is of the utmost importance. In our society, the transfer of goods and services is essential, enabling emergency response units to get their destinations in a timely fashion saving lives and property. Simply enabling our everyday citizens to travel as swiftly and safely as possible helps keep our city on an even tone. Citizens get to work on time and get home on time, but it does not stop there. Traffic Agents have pulled drivers to safety from burning vehicles. They have helped deliver babies and when necessary, they have captured or helped capture criminals. During the 9/11 terrorist attacks, it was a Traffic Agent working the Battery that first made the call about a low flying plane. Agent Calvin Francis and Ismal Quinones also distinguished themselves on September 11, 2001 by putting other lives in front of their own by helping to pull victims from the rubble to safety. In fact, on that day we had more heroes than we have space to mention. During the blackout and Hurricane Sandy, Traffic Agents worked around the clock to keep the city moving. When an Amber Alert was activated a Traffic Enforcement Agent was the one who was instrumental in observing the motorist and detaining him while responding officers arrived. Most recently, Traffic Enforcement Agents assisted in the Times Square terrorist attack on 5/8/17 and the lower Manhattan bike path attack of 10/31/17, not to mention the Con-Ed explosion in Chelsea on 7/19/18. Traffic Enforcement Agents are as necessary as the air we breathe.

You may not like to get that ticket or being asked to make a turn you do not want to make, but New York City Traffic Enforcement Agents are necessary for the good of our city and our mission to move traffic, save lives, move traffic, protect pedestrians, move traffic, reduce collisions. MOVE TRAFFIC, MOVE TRAFFIC, MOVE TRAFFIC.

Traffic Enforcement Agents perform work of varying degrees of difficulty in traffic enforcement areas in New York City. When required, they enforce laws and regulations involving moving and parked vehicles, including expediting the flow of traffic and prevent spillbacks; they’re doing blocking the box , Collision Auto reports, School crossing Initiative, Transportation outreach as part of vision zero to end the traffic fatalities and injuries; They help the public/tourists with information that they need and sometimes help them to cross the streets when it is possible. They testify at administrative hearing offices and in court, prepare required reports, and may be called upon to operate a motor vehicle. They’re saving lives and mainly reducing collisions in New York City. It is staffed with about 4,000 civilian uniformed traffic enforcement agents.